SEP & FRAND before the UPC - what has been happening in 2024?

November 22 2024 was a landmark date in the Unified Patent Court (UPC) – it was the date the UPC issued its first decision involving a SEP and a FRAND defence.

The Mannheim Local Division (LD) granted Panasonic an injunction enforceable in five European countries, dismissing OPPO’s FRAND objection and counterclaim.

The LD’s decision was based on the fact that OPPO had not provided any of its own data relating to its own sales. The LD considered a willing licensee would provide this data so that the potential licensor would be fully informed. The LD therefore held that OPPO was not a willing licensee. The FRAND defence was therefore unsuccessful, and the LD did not go on to consider any specific terms for a FRAND license.

An injunction was granted in relation to Germany, France, Italy, the Netherlands and Sweden (the UPCA countries in which the patent is in force). OPPO was also ordered to recall/destroy products as well as provide information, accounting and damage compensation.

Background

Panasonic sued OPPO for infringement of six European Patents: three before the Mannheim LD (EP2568724, EP3096315, EP2207270) and three before the Munich LD (EP2197132, EP3024163 and EP2584854).

OPPO submitted a counterclaim for revocation and a counterclaim for a FRAND licence.

The Mannheim LD decided to hear all aspects of the case i.e. the infringement, the counterclaim for revocation and the counterclaim relating to a FRAND licence.

Proceedings continued under EP2568724, with the proceedings in relation to the other five patents apparently being swept into the proceedings under EP2568724.

The patent was considered valid & infringed

After some claim construction issues, the LD held EP2568724 to be valid (dismissing the counterclaim for revocation) and infringed by OPPO's 4G smartphones and smartwatches.

The Mannheim LD then considered OPPO's counterclaim relating to a FRAND defence.

The FRAND defence

This is the first decision issued by the UPC that has considered a FRAND defence.

The Mannheim LD referred mainly to the Huawei v. ZTE judgment by the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) - (Case C-170/13). This July 2015 judgment is the defining EU jurisprudence on the granting of an injunction when FRAND obligations are involved and has ever-since shaped court practice across the EU in relation to SEP cases.

Huawei v. ZTE, CJEU Case C-170/13, July 2015

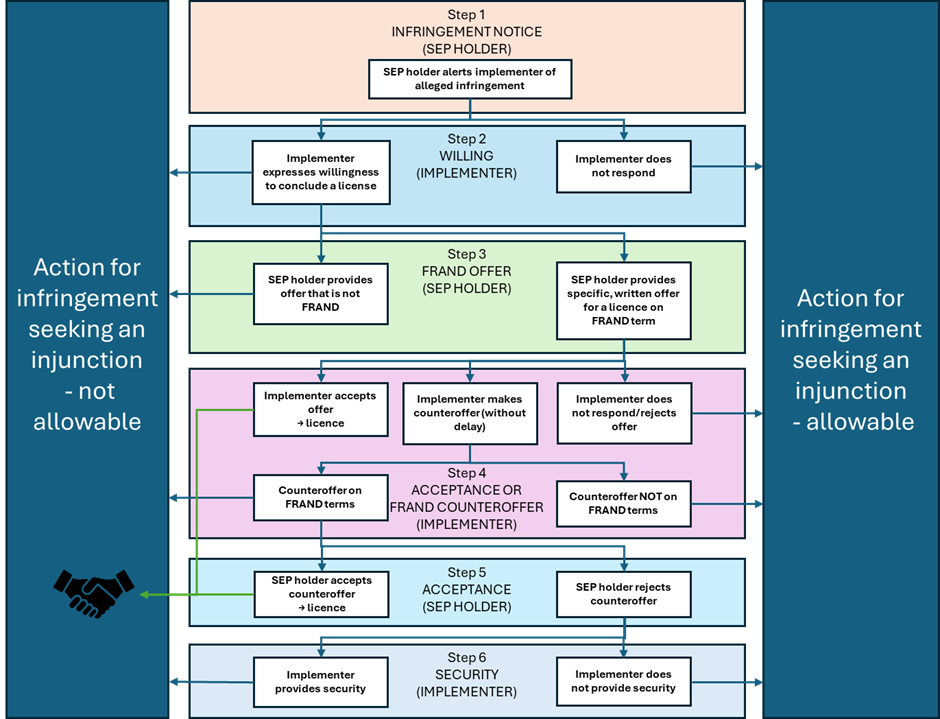

The outcome of Huawei v. ZTE is illustrated below.

According to Huawei v. ZTE, a SEP proprietor, which has given an irrevocable undertaking to grant a licence to third parties on FRAND terms, does not abuse its dominant position by bringing an action for infringement seeking an injunction as long as the following conditions are met:

- prior to bringing that action, the proprietor has:

- alerted the alleged infringer of the infringement complained about by designating that patent and specifying the way in which it has been infringed (Step 1), and,

- after the alleged infringer has expressed its willingness to conclude a licensing agreement on FRAND terms (Step 2), presented to that infringer a specific, written offer for a licence on such terms, specifying, in particular, the royalty and the way in which it is to be calculated (Step 3), and

- alerted the alleged infringer of the infringement complained about by designating that patent and specifying the way in which it has been infringed (Step 1), and,

- where the alleged infringer continues to use the patent in question,

- the alleged infringer has not diligently responded to that offer (step 4), in accordance with recognised commercial practices in the field and in good faith,

- this being a matter which must be established on the basis of objective factors and which implies, in particular, that there are no delaying tactics.

- the alleged infringer has not diligently responded to that offer (step 4), in accordance with recognised commercial practices in the field and in good faith,

A couple of subsequent steps (Steps 5 and 6) in relation to a counteroffer from the implementing alleged infringer were also defined, as illustrated below:

Since the CJEU judgment, national courts of the EU have repeatedly applied this framework of conditions. The questions the national courts have considered include:

- Does every SEP necessarily confer dominance to its holder?

- How detailed does an infringement notice need to be, particularly if a portfolio license is sought?

- When can the patent owner safely conclude that the user is an unwilling licensee and the seeking of an injunction is therefore justified?

- And, most importantly, how to determine a fair, reasonable, and non-discriminatory (‘FRAND’) license offer.

However, there has been some inconsistency across the EU states in regard to such questions. For instance, some national courts have decided that each step happens sequentially and that later actions cannot retroactively mean that an earlier step has been taken. Other national courts have decided that each step does not require sequentiality and that later actions can retroactively mean that an earlier step has been taken.

This has concerned the European Commission (EC) to such an extent that it recently took the rare step of filing an amicus curiae brief, in a patent infringement action pending at the Higher Regional Court Munich (6 U 3824/22 Kart HMD Global v. VoiceAge). The EC expressed its concern that the CJEU judgment was not being applied correctly and consistently across the EU.

The EC position's is that Step 1 requires specific details of the patent at issue and that it was not sufficient to just refer to, say, a website with general details of the SEP holder's SEPs. The EC also said that this has to happen before litigation starts and cannot be remedied later.

As far as Step 2 is concerned (which can be considered as ‘Willingness of Licensor’), the EC's position was that this needed to be explicit as well, and not conditional on things that might happen later.

The EC also indicated that all steps have to be taken before the injunction is sought, explaining that the purpose of the Huawei v. ZTE decision was to allow parties to negotiate without the fear of an injunction. The EC's view is that each step happens sequentially and that later actions cannot retroactively mean that an earlier step has been taken or not taken.

So what did the Mannheim LD decide?

The LD considered the willingness of the parties and ultimately dismissed OPPO’s defence on the facts of the case. The LD considered the offer from Panasonic to be FRAND but the counteroffer from OPPO not.

In considering OPPO’s counteroffer not to be FRAND, the decision relies on the fact that OPPO had not provided any of its own data relating to its own sales. The LD considered a willing licensee would provide this data, so that the potential licensor would be fully informed, and provide security on the resulting amount. The LD therefore held that OPPO was not a willing licensee.

The LD also considered the amicus curiae brief of the EC and concluded that each step does not require sequentiality and that later actions can retroactively mean that an earlier step has been taken.

Regarding the Infringement notice (Step 1), the Manheim LD said that “For good reason, however, the ECJ judgement does not impose any strict formal requirements at this point, but leaves it up to the courts of the Member States to decide on a case-by-case basis. Particularly in the case of an allegation of infringement of a large number of standard-relevant patents, a notice in the formalised form deemed necessary by the Commission may lead to confusion rather than the desired transparency”. [194]

The Mannheim LD therefore did not adopt the position encouraged by the EC for Step 1.

Turning to Step 2, again the position encouraged by the EC for Step 2 was not adopted, as the LD looked to later actions to define whether OPPO was a willing licensee.

The LD said an implementer seriously interested in a FRAND licence “would have raised a corresponding complaint at least once if it had actually had problems of understanding [details of the patent in suit] and asked for a more in-depth discussion. The defendants, on the other hand, did not raise any such objection, but only repeatedly requested further claim charts for other patent families” [195].

They went on to say "However, this does not mean that the further behaviour of both parties during the subsequent negotiations should be excluded from the assessment. Rather both the SEP holder and the implementer must behave "in accordance with commercial practice" during the negotiations and work in good faith towards the conclusion of a licence agreement. Their conduct must be assessed according to whether it takes sufficient account of the fundamental objective of the CJEU's negotiation programme to achieve the timely conclusion of a FRAND licence agreement on a primarily private-autonomous basis in targeted negotiations". [195]

“Nor is it in line with the ECJ's negotiation programme to examine the willingness of the implementer to take a licence alone, without sufficiently examining the SEP holder's offer, just as it would be insufficient to consider only the opposing offers and counter-offers after affirming the first two steps of the examination and to ignore the further conduct of the parties. This is because whether a (counter)offer meets FRAND criteria can only be assessed on the basis of the specific negotiations and the behaviour of the parties. Just as the implementer cannot make a favourable offer without sufficient knowledge of any licensing conditions granted to third parties, the SEP holder cannot make a favourable offer if the implementer deliberately leaves him in the dark about the extent of his acts of use and his economic framework conditions, such as the sales prices demanded by him on the market, and if he does not provide any information on the economic framework conditions of his actions, which conversely must be sufficiently plausible for the SEP holder - depending on the progress of the negotiations.” [201]

“Although - depending on the stage reached in the specific negotiations - it may not immediately be necessary to disclose one's own sales data in full, a licence seeker negotiating in good faith can nevertheless be expected to make available such data for certain partial periods of time which make it comprehensible to the SEP holder as a whole why the licence seeker feels entitled to calculate on its deviating basis, at least in order to check the plausibility of its own objections to the figures used by the other party”. [222]

The LD therefore decided that Panasonic had given sufficient notice of infringement (Step 1) and, although OPPO had expressed their initial willingness to take a licence in a sufficient manner to serve as a starting point for further negotiations, OPPO's subsequent conduct was not the conduct of a willing licensor (Step 2).

As the FRAND defence was unsuccessful, the LD did not go on to consider any specific terms for a FRAND license.

Would the UPC have set a global FRAND rate?

The LD stated that the “UPC has jurisdiction for the counterclaim filed by the defendants together with the statement of defence, which is aimed at determining a FRAND licence.”

The LD concluded “It can therefore be left open in the present case whether a determination of a specific FRAND licence rate by the court - even without a FRAND counterclaim by the implementer - can be considered, for example, if both parties have each submitted a (counter) offer within the FRAND corridor and then cannot agree on overcoming the remaining differences through a third party as considered by the ECJ (cf. ECJ loc. cit. para. 68).”

The LD therefore seems to have considered themselves competent to determine the FRAND license sought. However, the geographic scope of the licences proposed by OPPO were rejected as not relating to global terms.

The outcome in this case may have been different if OPPO had provided data relating to its own sales. The LD Mannheim discussed at length SEP FRAND obligations and the possibility of the UPC being a forum for FRAND-rate setting and they may have been prepared to consider rate-setting if the conditions were met.

So what is the way forward for SEPs and FRAND before the UPC?

How will the UPC and its various divisions proceed with SEP cases? We’ll see.

Other LD’s are currently considering actions involving SEPs: before the Munich LD we have Huawei v Netgear (ACT_459771/2023 UPC_CFI_9/2023) (decision due on 18 December 2024), Motorola v Ericsson (ACT_47298/2024 UPC_CFI_488/2024), and NEC v TCL (Access Advance as intervener) (ACT_595922/2023 UPC_CFI_487/2023); and before The Hague LD we have KPN v Orope (ACT_49150/2024 UPC_CFI_502/2024), filed in September 2024.

The only other decision so far dealing with a SEP (Philips v Belkin ACT_459762/2023 UPC_CFI_390/2023) was issued by the Munich LD and also granted an injunction (no FRAND defence was submitted in that case).

Both SEP decisions make it clear that the UPC will grant injunctions on SEPs. The approach taken by the Mannheim LD is similar to the general approach taken by the German national courts. National courts in other EU member states may have interpreted Huawei v ZTE in a way that is closer to the position encouraged by the EC in their amicus brief. It would be interesting to see a decision from a non-German Division of the UPC to see how, if at all, another Division of the UPC distinguishes its reasoning from that generally followed by the German national courts.

However the only SEP case pending before a non-German Division of the UPC (KPN v Orope, ACT_49150/2024), which is before The Hague LD, was only filed in September 2024 so it is some way off a decision.

The most seminal decision in The Netherlands for a FRAND defence in SEP cases is the July Wiko v Philips 2021 decision by the Supreme Court of the Netherlands. It will be interesting to see whether The Hague LD will follow the approach established by the UPC Mannheim LD or also decides to follow its ‘home practice’ and address a FRAND defence in the way followed by national courts in The Netherlands.

With the decision in relation to Huawei v Netgear due on 18 December 2024, time will tell whether other divisions of the UPC will follow the Mannheim LD approach. And any appeal to the Court of Appeal may of course add a twist to this tale.