Mass claims across borders: a deep dive into the Netherlands, England & Wales, and Germany

Collective actions are a hot topic in Europe and Asia-Pacific, diminishing the historically big gap between these jurisdictions and the US. In this deep dive we focus on three major litigation European jurisdictions, the Netherlands, England and Germany, and consider the collective redress action regime in these jurisdictions. We examine the way each has constructed its collective redress action mechanism, consider recent case law and the trends we are seeing which claimants and defendants should be aware of in the next year.

As flagged in an earlier article about the continuing rise of consumer claims in the EU, the enactment of the Representative Actions Directive (“RAD”) in December 2020 meant that each EU Member State had to create a regime for bringing collective redress actions on behalf of groups of claimants against infringements by traders of specific EU laws. Most Member States have complied since (see our Tracker for more detail).

As a Directive the RAD will have varying effects across Member States. The RAD contains minimum requirements and it only requires the domestic implementation of an opt-in mechanism, although individual jurisdictions may choose to go a step further and introduce opt-out mechanisms. Under the Directive, so-called "Qualified Entities" (QEs) may bring a collective redress action on behalf of groups of claimants harmed by unlawful practices which breach specific EU laws. Nevertheless, the most significant impact of the Directive is that it allows claimant groups to seek injunctive measures but also redress measures. Or, in other words: compensation and similar remedies, which should make it much easier and more effective for consumers across the EU to seek compensation; something that was often not possible in many Member States. As a general trend, the Directive will encourage more class actions in the years to come, as it provides the first EU wide harmonised framework for class actions, it improves the access to compensation and due process for consumers, and establishes safeguards against exploitative litigation.

However, class-action regimes across Europe are still not created equal. This is primarily because, as mentioned above, some Member States already have well-developed class action regimes and others are or remain underdeveloped. Despite such harmonisation efforts, involved parties – whether they be plaintiff groups, litigation funders, or corporations faced with a mass claim – may still encounter vast differences within not only the EU, but also the United Kingdom (specifically England & Wales) which still plays a major role within the broader European economy and often remains the jurisdiction of choice for commercial contracts.

Find out more about the collective redress action regime in each of our selected jurisdictions below:

The Netherlands: WAMCA (Act for the Settlement of Mass Damages in Collective Actions)

The Netherlands has historically been at the forefront of developments in collective redress in comparison to both the UK and other EU Member States.

The Netherlands has had a class action procedure since 1994, but victims were made to seek damages before the civil court individually, where the burden of proof was on their part. This also created pressure on the judicial system, which was overwhelmed with individual cases. The Dutch legislator sought to partially remedy this by introducing a new regime in 2005 (the Collective Settlement of Mass Damages Act, or ‘WCAM’), that allowed courts to declare settlements universally binding for all victims, regardless of their participation in the settlement (Dutch Civil Code, Article 7:908). Still, there was neither a collective compensation scheme nor a relief of pressure on the judicial system.

Fifteen years later, this was remedied through the introduction of the new Act for the Settlement of Mass Damages in Collective Action (‘WAMCA’) which enables civil courts to award compensation in collective redress action cases and is considered a major improvement over its predecessors. The WAMCA not only allows for the awarding of direct and collective damages to claimants, but furthermore provides for an opt-in mechanism for foreign claimants (i.e., potential claimants need to actively sign up to take part) and specifically an opt-out mechanism for Dutch class action members (i.e., nobody needs to sign up, everybody who falls within the scope of the claim is entitled to join the action). The WAMCA also includes a series of admissibility requirements which must be met by the representative bodies to qualify for a class action.

The WAMCA is today considered amongst the most highly sophisticated collective redress regimes within the EU, and even after the enactment of the RAD stands out from other EU regimes. This development can be mainly attributed to two key aspects of the WAMCA: (1) simplicity and (2) finality. Not only did the WAMCA simplify initiating mass claims for breach of contract or tort, but it also offers a comprehensive collective compensation scheme for potential large claimant groups with nuanced opt-in and opt-out features. This makes the WAMCA attractive for both plaintiffs and defendants. Plaintiff groups are, on the one hand, forced to work together and can more easily pool their resources. It also facilitates raising collective funding from third parties, such as litigation financiers. On the other hand, defendants effectively know where they stand in terms of exposure after the proceedings have come to a close.

The WAMCA therefore offers efficient adjudication of claims involving large groups of claimants by ensuring that all stakeholders are bound by the outcome of a single judicial procedure, instead of each plaintiff having to start individual proceedings. This is mainly achieved through the system of so-called ‘special interest groups’ and the ‘opt-out’ mechanism for Netherlands-based class members:

- Claimants do not litigate individually but through special purpose vehicles known as ‘special interest groups’ or ‘representative bodies’, who usually decide to incorporate themselves as a non-profit foundation. These special interest groups represent the joint interests of the claimants and advocate on their behalf before the court. If there are multiple special interest groups, the court appoints one as the ‘exclusive representative’ in the proceedings. This exclusive representative then acts as the leading claimant who performs (i) all procedural steps, (ii) serves as the coordinating (primary) point of contact for both the court and the defendant, and (iii) manages the interests of the other special interest groups and their constituencies as well as any injured parties not affiliated with a particular special interest group. In most cases, the court will only appoint one exclusive representative, although the WAMCA allows for appointing multiple co-representatives which is subject to the discretion of the court.

- The outcome of WAMCA-proceedings is also automatically binding for all Netherlands-based injured parties who fall within scope of the claim, unless they actively choose to opt-out from the proceedings or a settlement. This applies not only to actual members of the special interest group(s) who actively choose to become involved in the collective redress action, but also to injured parties that did not make such a decision and whom might not even be aware of the proceedings’ existence; if they fall within the scope of the group as defined by the court (referred to as the ‘narrowly defined group’), they are bound by the outcome of the WAMCA-proceedings, unless they opt-out in time. Foreign injured parties that fall within the scope of the narrowly defined group still need to actively sign-up to the action (‘opt-in') to be bound by the proceedings’ outcome.

This system has several advantages. The opt-out mechanism increases the likelihood of finality: the vast majority of claimants are unlikely to opt out. This, in turn, significantly reduces the likelihood of a flood of cases being brought by late adopters. In other words, the WAMCA is designed to achieve as much finality as possible around a particular type of claim against a particular defendant. This not only reduces the pressure on the judicial system, but also limits the ongoing uncertainty for defendants, who will effectively know where they stand once the legal proceedings initiated by some of the first movers have been concluded. It also concentrates the litigation between claimants and defendants in a single court case, allowing claimants to pool their resources and effectively reduce the overall cost of litigation.

In addition to providing a single point of contact for the defendant and the courts, the special interest groups also provide for a central fundraising vehicle that can raise capital necessary to cover the significant costs of litigation; costs that individual claimants might otherwise not be able to pay. This promise of efficient collective redress has attracted many litigation funders who advance the costs for the litigation in exchange for a percentage of the recovery (if any), who find the notion of efficient adjudication for large groups of claimants an attractive proposition.

Disadvantages: ‘admissibility limbo’?

Despite its obvious advantages, the WAMCA is far from perfect in practice. As we noted in an earlier contribution, the WAMCA has since its enactment in 2020 led to the filing of 96 collective claims that to date has resulted in just one substantive judgment concerning mass damages. Critics attribute this slow turnover rate to the strict admissibility requirements the WAMCA imposes on special interest groups, as well as formalities that provide ample opportunity to raise procedural hurdles:

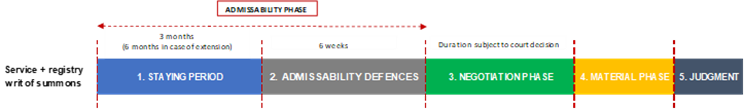

- Following the service of a writ of summons to a defendant, the special interest group must register the writ of summons in a central register for WAMCA-claims. This registration triggers a three-month standstill period to allow other potential special interest groups to also file a claim, which period can be extended for a further three months. The proceedings are then effectively suspended.

- After the mandatory standstill period has ended, the defendant has six weeks to submit a statement of defence. The defendant may choose to limit its defence initially to procedural admissibility arguments, which may cause significant additional delays:

- First, special interest groups must meet strict requirements. They must demonstrate proper governance, oversight, and transparency. They must also prove financial resources sufficient to cover legal costs, as well…